Wildlife Research Assistant Fellowship Phoenix Zoo & ASU

Posted on January 9, 2016 Leave a Comment

Wildlife Corridor Research, using motion activated cameras to capture species utilization of water supply in Arizona.Works with the Conservation Research Fellow, both in the field and in the office, with the initiation and implementation of the Verde River Wild Water project. Responsible for learning and applying wildlife survey and research techniques in often very remote wilderness locations. Field sites are accessed by All-terrain vehicle, inflatable kayaks and on foot. Majority of the time is expected to focus on image identification and analysis.

Assistant to Researcher and Post-Doc Fellow, Jan Schipper with the Phoenix Zoo’s Conservation Department.

Posted on November 1, 2012 Leave a Comment

Graphic Designer and Sales Representative for Mostly Postcards, Inc. from 2005 to 2012.

Esri & National Audubon Society

Posted on July 24, 2012 Leave a Comment

User conference 2012 was my first exposure to ESRI, and my mouth dropped open. I was grateful for the opportunity to attend with funding through The National Audubon Society who paid for my registration, meals and stay for the week.

During the conference, I had a plethora of talks to go to, I focused on the conservation topics mostly but also went to a lot of spatial analysis talks. I was amazed at the projects and research organizations where conducting via GIS.

I also had the opportunity to table for The National Audubon Society where we discussed the recent establishment of the migratory pathways that the researchers developed through GIS analysis. As I walked around the nonprofit section, I felt like I died and gone to heaven all the BIG NGOs were there; The Nature Conservancy, Nature Serve, Wildlife Conservation Society, World Wildlife Fund, National Geographic, Earth institute, World Health Organization and many more .

I absolutely enjoyed the conference and look forward to seeing more great research from GIS for conservation planning.

Urban Hummingbird Project

Posted on June 16, 2012 Leave a Comment

In partnership with the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the City of Phoenix and Audubon Arizona[1] launched a new outreach program called the Urban Hummingbird Program that I was hired to manage. Objectives of this program were to educate elementary school children about central Arizona’s hummingbirds. Students would learn how to identify common species and discover natural history facts that make hummingbirds so amazing. Additionally, kids were educated how to help these magnificent birds by planting native plants and by participating in a kid-friendly citizen-science monitoring program.

I helped Audubon Arizona meet these program objectives by managing and continuing to develop and fine tune the in-class presentation and materials; including a power point show, workbook and hummingbird migration game. Classes would receive a free “Arizona Hummingbird Box” containing a hummingbird feeder, an attractive hummingbird identification wheel, pencils and directions for collecting and submitting classroom hummingbird observations to the National Phenology Network[2], a national database that tracks animal migration timing and other natural events. The program was a success; goals were set to connect with 300 students that I surpassed by reaching close to 3,000. Not only were the teachers and students enthusiastic about what the program offered, the Urban Hummingbird Program was also recognized with a Merit Award by Valley Forward for Environmental Education Excellence in 2012, which I chosen to receive on behalf of Audubon Arizona. I’ve included a referral letter from lead teacher/naturalist about my work ethic and accomplishments while working alongside her.[3]

During my work at Audubon Arizona’s Nina Mason Pulliam center, I lead nature walks, developed summer, winter and spring break programs as well as traveled to libraries and museums giving presentations and sharing my enthusiasm for birds and the environment with the public. I believe this opportunity opened my eyes to the world of education and my love of sharing our Earth’s wonder with not only students but with engaged citizens.

I love that Audubon Arizona has extended this citizen science program to collecting hummingbird observations in your backyard with “Hummingbirds at Home”.

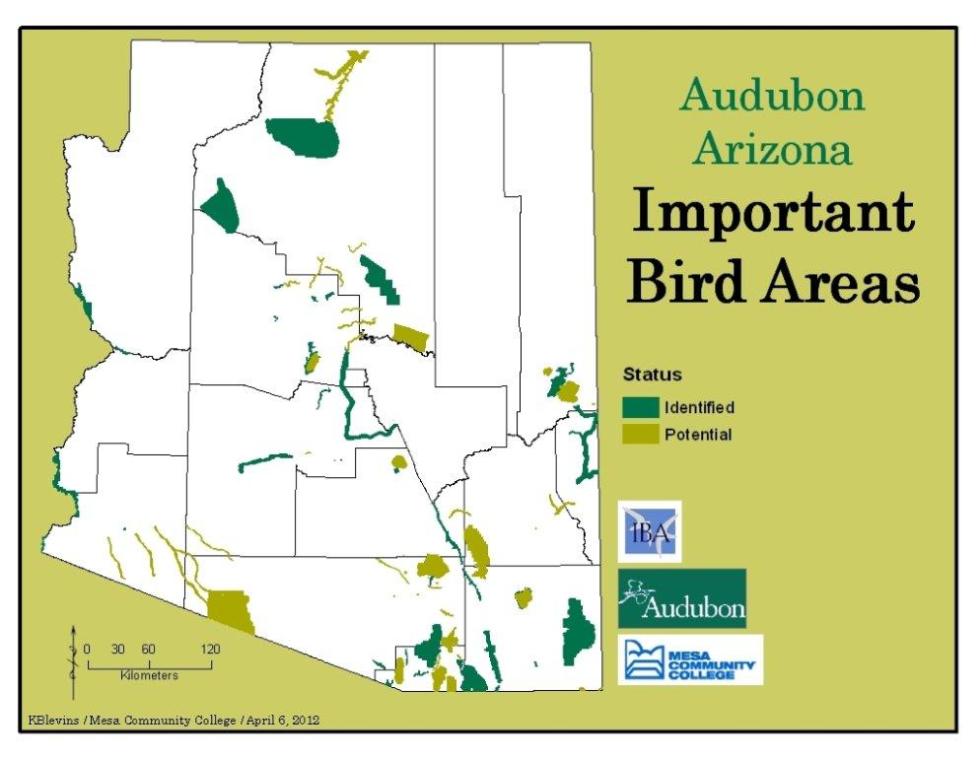

Important Bird Area Mapping for Audubon Arizona

Posted on May 31, 2012 Leave a Comment

2 year internship starting from concept and finishing with a map book highlighting the Important Bird Areas in Arizona. I was interviewed about the internship, please read about the opportunity in an article here. In addition, my capstone for my Certification in Geospatial Technologies analyzed the species of greatest concern using spatial statistics technique of Regression Analysis to find gaps in protection. This analysis was used to locate where Audubon Arizona should be focusing on to add necessary Important Bird Area sites. The data was based on bird distributions for species of greatest concern. Bird distribution data from Arizona Game and Fish was used for the analytics . Read more about AZ’s Important Bird Area program here.

2 year internship starting from concept and finishing with a map book highlighting the Important Bird Areas in Arizona. I was interviewed about the internship, please read about the opportunity in an article here. In addition, my capstone for my Certification in Geospatial Technologies analyzed the species of greatest concern using spatial statistics technique of Regression Analysis to find gaps in protection. This analysis was used to locate where Audubon Arizona should be focusing on to add necessary Important Bird Area sites. The data was based on bird distributions for species of greatest concern. Bird distribution data from Arizona Game and Fish was used for the analytics . Read more about AZ’s Important Bird Area program here.

Our Draft report below:

Assessment of Conservation Priority for Arizona IBAs:

Bird Conservation Planning Using Geospatial Analysis and Threats Scoring Criteria

A Draft Report of the

Important Bird Areas Program

Audubon Arizona

by

Tice Supplee, Director of Bird Conservation

Lindsey Hendricks, GIS Analyst

Jennie MacFarland, IBA Coordinator

Draft date July 30, 2012

****DRAFT CURRENTLY IN REVIEW, NOT FOR CIRCULATION****

Abstract

Important Bird Areas are sites that provide essential habitat for one or more species of bird. IBAs include sites for breeding, wintering, and/or migrating birds. IBAs may be a few acres or thousands of acres, but usually they are discrete sites that stand out from the surrounding landscape. IBAs may include private or public lands, or both, and they may be protected or unprotected.

Important Bird Areas Assessment is a key component of any conservation strategy since it is the method by which we track Important Bird Areas. The IBA assessment approach focuses on three essential elements – (1) conservation targets (birds & habitats), (2) threats (scope, severity, permanence), and (3) conservation activity (designation, planning, actions).

Audubon in Arizona has identified 42 Important Bird Areas over a ten year period. Of these eight have been given Global priority by National Audubon Society and 7 additional Arizona Important Bird Areas are being considered for global designation. Two additional sites will be evaluated by our IBA Science Committee in the fall of 2012 and we anticipate 2-3 additional sites in our list of 48 remaining potential areas will be considered in the next 2-3 years.

In order to provide a holistic, landscape view of the IBA process, we developed a spatial modeling approach that evaluates both priority habitats and distribution of bird Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) identified in the Arizona Game and Fish Department State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP). Our model is based on breeding bird distribution as mapped in the Arizona Breeding Bird Atlas (Corman and Gervais-Wise 2004) and land cover data from the Southwest ReGAP Program a division of the National Gap Analysis Program – “Gap analysis” refers to a specific, stepwise method of assessing and mapping the level of biodiversity protection for a given area. The SGCN and habitats analysis for Arizona IBAs was completed by students enrolled in the Mesa Community College Geospatial Analysis certification program. Further refinement of these products will continue, beginning with those IBAs ranked as highest priority through an Arizona priority ranking analysis using these models and other inputs related to level of protection, threats and opportunities.

Each Important Bird Area was also “Scored” based upon the following criteria: presence of threats to the habitats or focal bird species, qualification of the IBA for Global or Continental importance, presence of unique habitats and/or assemblages of species groups (waterfowl, waterbirds, shorebirds, migrants, raptors, biome restricted assemblages), level of land protection, and capacity for conservation and monitoring activities.

Introduction

Arizona Game and Fish Department developed a scoring criterion for species occurring in the state to rank them into tiers of conservation importance. The resulting list are Arizona Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) presented in three Tiers and the top Tier 1 further split into “a” and “b”. National Audubon Society has identified species of birds at a global and continental scale that are in need of conservation attention and protection. These species are periodically updated into a Red and Yellow WatchList using trend data from Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) and Christmas Bird Counts (CBC). There is a high level of overlap between the two lists, although there are some species given priority by Arizona Game and Fish Department that are not on the Audubon Watchlist and the reverse. An approach for this project is to quantify Audubon WatchList species priorities at IBAs through the Global and Continental identification of IBAs. Appendix A. presents the list of Arizona SGCN and WatchList bird species that are considered for qualifying a site as an Arizona Important Bird Area. An objective of this project was to complete a spatial assessment that focused on identifying those IBAs that offer habitats for Arizona State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP) Tier 1a and Tier 1b avian species.

The Arizona Bird Conservation Initiative has identified habitats of highest ecological importance for avian conservation in Arizona. The members of the Arizona Important Bird Area Science Committee agreed in October, 2012 that Arizona IBAs should be ranked in relative priority based upon the percent occurrence of these habitat types within the IBA. A second objective of this project was to calculate the percentage of each Arizona IBA that was composed of the following habitats: riparian, wetlands and associated open water, montane mixed conifer forest, sub-alpine conifer forest (aspen, spruce and fir), grasslands (plains, Great Basin, semi-desert, sub-alpine), Madrean pine and oak woodlands and savannahs, and Sonoran desert).

One of the global IBA criteria established and implemented worldwide by BirdLife International pertains to biome-restricted species assemblages. Through this criterion, IBAs are identified if a site is known or thought to hold a significant component of the group of species whose distributions are largely or wholly confined to one global biome (applies to groups of species with distributions of > 50,000km2, which occur mostly or wholly within all or part of a particular biome and are of global importance). This criterion relates to sites that support groups of species that may be common within the planning area (e.g. country), but are not widespread outside of the planning area. These species can be thought of as those for which the planning unit has responsibility for their long-term conservation. Applying this criterion at geographic scales smaller than the global scale requires stepping down to scale-appropriate components of the criterion. In North America, North American Bird Conservation Initiative’s Bird Conservation Regions (BCRs; http://www.nabci-us.org/) are used as surrogates for global biomes. BCRs are ecological units derived for the purpose of planning and implementing bird conservation in North America; portions of four BCRs comprise Arizona (see Figure 1).

Important Bird Areas (IBA) Assessment

Initially, Important Bird Areas are selected as based on the particular species of bird(s) and the number(s) of individuals that occur at the site. As part of this identification process, data are compiled about the habitats, threats, landuse, and ownership of the site. These data provide an initial snapshot of the quality of the site and allow decisions to be made about the site’s merit as an Important Bird Area. While these data are critical in making the initial determination of a site’s status, for the long term conservation and management of the Important Bird Area the birds, habitat, threats and other site characteristics need to be periodically evaluated.

Figure 1. The four Bird Conservation Regions (BCRs) of Arizona

The data resulting from the assessment process can then be applied to conservation decision making. IBA Assessment data are used not just to determine what conservation actions may be appropriate to take, but also in evaluating the success of previously taken conservation actions. The Arizona Important Bird Area spatial analysis and assessment serves as an initial baseline for future evaluation of conservation accomplishments and status of sites identified as important for the conservation of birds in Arizona.

Methodology

Overall Goal and Objectives

Overall goal: Identify the most important identified IBAs in Arizona for Conservation

Objective 1a: Analyze the Breeding Bird Atlas SGCN Tier 1a and Tier 1b overlay with the 42 Arizona identified IBAs

- Develop GIS analysis for each Tier 1a and Tier 1b avian SGCN

- Develop GIS analysis layer for identified Arizona IBAs,

- Create and apply ranking system to combine information from a and b.

Objective 1b: Score all IBAs for the number of Tier 1a and Tier 1b species that occur at each IBA and have additional state qualifying criteria for species assemblages of state significance including concentrations of species (raptors, waterbirds, waterfowl, and migration bottlenecks).

- State Tier 1a Species: 3 points per species

- State Tier 1b Species: 1 point per species

- Species Assemblage (Sonoran desert species, hummingbirds, warblers) and Species Concentration (raptors, waterfowl, waterbirds, and migration bottlenecks) : 2 points each

Objective 2: Analyze the percent presence of priority vegetation and habitat types using vegetation coverage from Southwest ReGap as edited by the Arizona Game and Fish Department. The vegetation types identified as priority for avian species in Arizona are: Riparian, Marsh, Wetlands, Aspen, All grasslands, Madrean oak woodlands, Upper and lower Sonoran desert, and both Montane and Subalpine conifer forests. Scores are assigned to each IBA from 1-5 based on percent of these habitats represented within the IBA.

- Develop vegetation community maps for each of the 42 Arizona IBAs.

- Create and apply a vegetation community ranking system

Objective 3: Score each identified Arizona IBA for threat vulnerability, Global and Continental Watch List bird species importance, level of land protection, and current capacity for conservation and monitoring activities.

- Score each IBA for threats vulnerability levels

- Score each IBA for Global and Continental species values

- Score each IBA for level of land protection

- Score each IBA for conservation and monitoring capacity

- Each IBA was scored by evaluating the level of identified threat using Conservation Open Standards analysis looking at three factors; scope of threat – is it pervasive throughout the IBA or limited to a portion of the IBA; intensity of the threat – are the impacts minor or severe; reversibility of the threat – if abatement action is taken can the threat be easily reversed. A value could also be assigned to identified future threats related to the immediacy of the threat – is it likely to occur in the short term or at a more distant unknown time.

Threat Scores: High impact: score 8–12; Medium impact: score 6–7; Low impact: score 3–5. High impact threats were multiplied by 3 times and Moderate impact threats were multiplied by 2 times.

- Global and Continental IBAs were scored the same at 5 points for the designation and 2 extra points for each additional global or continental qualifying species. Both currently recognized global and continental IBAs and nominated IBAs entered into the National Audubon Society database were scored under these criteria. IBAs that have both a global and continental designation were assigned 10 points. Details about the qualifying criteria for the named species are located in Appendix XXX.

Global Designation: IBA has sufficient population of the following qualifying species: California Condor, Black Rail, Spotted Owl, Pinyon Jay, Bell’s Vireo, Bendire’s Thrasher, Chestnut-collared Longspur and concentrations of Yuma Clapper Rail, Sandhill Crane, Neotropic Cormorant, Clark’s Grebe.

Continental Designation: IBA has sufficient population of the following qualifying species: Scaled Quail, Montezuma Quail, Clark’s grebe, Yuma Clapper Rail, Long-billed Curlew, Elf Owl, , Blue-throated Hummingbird, Costa’s Hummingbird, Rufous Hummingbird, Elegant Trogon, Lewis’s Woodpecker, Arizona Woodpecker, Gilded Flicker, Willow Flycatcher, Mexican Chickadee, LeConte’s Thrasher, Virginia’s Warbler, Lucy’s Warbler, Grace’s Warbler, red-faced Warbler, Abert’s Towhee, Rufous-winged Sparrow, Brewer’s Sparrow, Black-chinned Sparrow, Lark Bunting, McGowan’s Longspur.

- Protection Level Scoring (Low numbers equal high level of protection): 1= National Park, Preserve (State or Private), National Wildlife Refuge; 2=National Monument, National Conservation Area, Wilderness Area, State Wildlife Area, Conservation Easement; 3=State, County, City Parks, USFS, BLM, DofD, Tribal and Communal Lands with designated management for natural resources; 4=State Trust Lands, Private Lands, Tribal and Communal Lands; 5=lands identified for development.

- Stewardship and/or monitoring was assigned scores of 1=very low capacity where there is no current monitoring and poor eBird coverage; 2=medium capacity with available data sources from eBird, CBC, or other structured surveys (marshbirds, sandhill cranes, winter waterfowl, agency surveys); 3=high capacity with an active Audubon or Friends group conducting IBA avian surveys, University or agency research or inventory, or high quality contributing data to eBird.

Study Area

The study area of this project was the 42 identified Important Bird Areas in the state of Arizona as of January 2012.

Methods

Data & Software Overview:

- BCR – Bird Conservation Region

North American Bird Conservation Initiative

- ArcView Data – Vector

- SWReGap – Southwest Regional Gap Analysis – USGS

- Landcover

- ArcView Data – Raster

- Project to UTM Zone 12 N, meters

- Stewardship

- ArcView Data – Vector

- Project to UTM Zone 12 N, meters

- ArcView Data – Vector

- ArcView Data – Raster

- Landcover

- Audubon Arizona Important Bird Area – Audubon AZ & MCC

- ArcView Data – Vector

- Vegetation

- Rivers

- Elevation

- Roads

- County

- BBA – Breeding Bird Atlas –

- ArcView Data – Vector

AZ Game & Fish

- Access Database, without Native American lands

- Join with quads

IBA Priority Scores are relative to each other. Scores include favoring sites with existing stewardship and monitoring capacities (up to 3 additional points). The highest scoring IBAs are sites with best combination of factors for focused conservation work. IBAs Highlighted in Gray have a current commitment of IBA Program Resources.

Table 1. Assemblages of responsibility species for priority habitat types within Arizona Bird Conservation Regions (BCRs)

| Southern Rockies/Colorado Plateau (BCR 16) Southern Rockies | Sonoran and Mohave Deserts

(BCR 33) Sonoran & Mohave |

Sierra Madre Occidental

(BCR 34) Madrean |

Sierra Madre Occidental

(BCR 34) Continued |

| Forest

Dusky Grouse Northern Goshawk Golden Eagle Mexican Spotted Owl Northern Pygmy Owl Lewis’s Woodpecker Gray Jay Olive-sided Flycatcher MacGillivray’s Warbler Red-faced Warbler Olive-sided Flycatcher MacGillivray’s Warbler Evening Grosbeak Pine Grosbeak

Aspen Cavity nesting assemblage

Grassland Mountain Plover Ferruginous Hawk Western Burrowing Owl Common Nighthawk Savannah Sparrow

Riparian Woodland and Streams SW Willow Flycatcher Pacific Wren American Dipper Black-billed Magpie Swainson’s Thrush Lincoln’s Sparrow

Wetland and Open Water Bald Eagle Peregrine Falcon American Bittern

|

Sonoran Desert

Golden Eagle Snowy Plover Gila Woodpecker Gilded Flicker Elf Owl Cactus Ferruginous Pygmy Owl Western Burrowing Owl Black-capped Gnatcatcher Desert Purple Martin LeConte’s Thrasher Rufous-winged Sparrow

Grassland Cassin’s Sparrow Rufous-winged Sparrow (semi-desert grasslands)

Riparian Woodland Bald Eagle Mississippi Kite Western Yellow-billed Cuckoo Broad-billed Hummingbird Thick-billed Kingbird SW Willow Flycatcher Bell’s Vireo Yellow Warbler Lucy’s Warbler Abert’s Towhee

Wetland and Open Water Clark’s Grebe Peregrine Falcon California Black Rail Yuma Clapper Rail Long-billed Curlew Sandhill Crane Sprague’s Pipit (winter)

|

Forest

Northern Goshawk (Apache) Golden Eagle Northern Pygmy Owl Mexican Spotted Owl Magnificent Hummingbird Olive-sided Flycatcher MacGillivray’s Warbler Red-faced Warbler Olive-sided Flycatcher MacGillivray’s Warbler Yellow-eyed Junco Evening Grosbeak

Aspen Cavity nesting assemblage

Grassland Scaled Quail Masked Bobwhite Quail Western Burrowing Owl Common Nighthawk Azure Bluebird Chestnut-collared Longspur (winter) McGowan’s Longspur (winter) Brewer’s Sparrow (winter) Arizona Botteri’s Sparrow Arizona Grasshopper Sparrow Western Grasshopper Sparrow

Riparian Woodland Violet-crowned Hummingbird Elegant Trogon Broad-billed Hummingbird Blue-throated Hummingbird Thick-billed Kingbird SW Willow Flycatcher Sulphur-bellied Flycatcher Rose-throated Becard Bell’s Vireo Western Yellow-billed Cuckoo Swainson’s Thrush Gray Catbird Yellow Warbler Lucy’s Warbler

|

Madrean Oak Woodland

Montezuma Quail Gould’s Turkey Mexican Spotted Owl Whiskered Screech Owl Common Nighthawk Mexican Whip-poor-will Buff-collared Nightjar Magnificent Hummingbird Blue-throated Hummingbird Arizona Woodpecker Dusky-capped Flycatcher Buff-breasted Flycatcher Mexican Chickadee Five-stripped Sparrow

Wetland and Open Water Wood Duck Sandhill Crane Sprague’s Pipit (winter)

Chihuahuan Desert (BCR 35)

Grassland Scaled Quail Western Burrowing Owl Azure Bluebird Chestnut-collared Longspur (winter) McGowan’s Longspur (winter) Brewer’s Sparrow (winter) Arizona Botteri’s Sparrow

|

Because some Species of greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) are relatively common in Arizona, we were not looking to score an IBA at every site where a SGCN occurs. Rather, we took a reserve design approach and sought to identify IBAs where high priority identified habitats supporting SGCN occurred at significant percentages. A scoring and ranking system was developed using the calculated percentage of priority habitats occurring in each IBA. We defined “most important” as sites with the largest, most intact (e.g. least fragmented) patches of habitat that support the highest richness of responsibility species comprising each assemblage and with the greatest chance of long-term protection.

References

Boykin, K.G., L. Langs, J.Lowry, D. Schrupp, D. Bradford, L. O’Brien, K. Thomas, C. Drost, A. Ernst, W. Kepner, J. Prior-Magee, D. Ramsey, W. Rieth, T.Sajwaj, K. Schulz, B. C. Thompson. 2007. Analysis based on Stewardship and Management Status. Chapter 5 in J.S. Prior-Magee, ed. Southwest Regional Gap Analysis Final Report. U.S. Geological Survey, Gap Analysis Program, Moscow, ID. Available on-line at: http://fws-nmcfwru.nmsu.edu/swregap/.

Brown, Dave. 1994. Biotic Communities: Southwestern United States and Northwestern Mexico. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Burger, M., Halperin, J., Liner, J., Draft 2004. Identification of IBAs: Bird Consevation Planning Using GAP Analysis Data. Audubon New York.

Corman, T., Latta, M., & Beardmore, C. 1999. Arizona Partners in Flight Bird Conservation Plan. Technical Report 142. Nongame and Endangered Species Program, Arizona Game and Fish Department. Available on-line at: http://www.azgfd.gov/pdfs/w_c/partners_flight/APIF%20Conservation%20Plan.1999.Final.pdf

Esri. 1999. Environmental Systems Research Institute. Redlands, CA.

International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN). 1980. World conservation strategy: living resource conservation for sustainable development. IUCN-UNEP-WWF. Gland, Switzerland.

Liner, Jillian. Summer 2004. Audubon Uses GIS to Identify Important Bird Areas in New York State. ESRI, ArcNews Online. Available on-line at: http://www.esri.com/news/arcnews/summer04articles/audubon-uses.html

Appendix A. Data sources.

| Dataset | Originator | Publication date | Title | Acquired from | Type | Projection |

| Arizona-GAP land cover | USGS | Raster | UTM Zone 18 north, meters | |||

| AZ-GAP species distributions | USGS | Raster | same

|

|||

| SW-GAP stewardship lands | Jan. 2001 | USGS | Vector | same

|

||

| SW-GAP Ecozone Coverage | USGS | Vector | same

|

|||

| Arizona

Wildlife Habitat Fragmentation |

Arizona Game and Fish Department | June 1999 | NYS Route System | AGFD HabiMap | Vector | same

|

| Important Bird Areas | Audubon Arizona | June 2012 | Important Bird Areas of Arizona | Audubon Arizona | Vector | same |

Appendix B. Flowchart of data analysis.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Appendix C. Ecoregional stratification of potential Important Bird Area Hot Block assessment.

Hectares is the area of assemblage habitat within each ecoregion.

% of Grand total is the ecoregion habitat hectares divided by the Grand Total.

Ecoregions with % of Grand total not in bold were dismissed from further analysis.

** Bird Conservation Region and ecoregion boundaries do not always coincide. Therefore, some

ecoregions were fragmented by the BCR boundaries and had relatively little area. In BCR 13, the

St. Lawrence, Lake Champlain, and northern portions of the Adirondack ecoregion were joined

together to make one ecoregion we termed the ‘Northern Tier’.

| BCR 28 Shrub | Appalachian Plateau | Catskill Mountains | Hudson Valley | Lower Hudson | Mohawk/Black River Valley | Grand Total |

| Hectares | 438,256 | 23,397 | 16,482 | 1,408 | 757 | 480,302 |

| % of Grand total | 0.91 | 0.05 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | |

| Habitat in Hot Blocks (ha) | 138,701 | |||||

| % Habitat in Hot Blocks | 0.32 | |||||

| Habitat in Hot Block IBAs | 2,700 |

| BCR 28 Grassland | Appalachian Plateau | Catskill Mountains | Hudson Valley | Lower Hudson | Mohawk/Black River Valley | Grand Total |

| Hectares | 730,264 | 66,001 | 44,119 | 2,831 | 3,339 | 846,556 |

| % of Grand total | 0.86 | 0.08 | 0.05 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | |

| Habitat in Hot Blocks (ha) | 207,136 | |||||

| % Habitat in Hot Blocks | 0.28 | |||||

| Habitat in Hot Block IBAs | 0 |

| BCR 28 Forest | Appalachian Plateau | Catskill Mountains | Hudson Valley | Lower Hudson | Mohawk/Black River Valley | Grand Total |

| Hectares | 1,545,242 | 757,906 | 219,198 | 122,301 | 3,071 | 2,647,720 |

| % of Grand total | 0.58 | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.05 | < 0.01 | |

| Habitat in Hot Blocks (ha) | 452,783 | 464,102 | ||||

| % Habitat in Hot Blocks | 0.29 | 0.61 | ||||

| Habitat in Hot Block IBAs | 26,559 | 18,230 | 28,852 | 12,706 |

| BCR 13 Shrub | Appalachian Plateau | Great Lakes Plain/SW Tug Hill | Hudson Valley | Northern Tier | Mohawk/Black River Valley | Grand Total |

| Hectares | 249,166 | 533,475 | 11,652 | 295,491 | 93,472 | 1,183,258 |

| % of Grand total | 0.21 | 0.45 | 0.01 | 0.25 | 0.08 | |

| Habitat in Hot Blocks (ha) | 79,178 | 264,742 | ||||

| % Habitat in Hot Blocks | 0.31 | 0.50 | ||||

| Habitat in Hot Block IBAs | 2,050 | 23,400 | 43,463 |

| BCR 13 Grassland | Appalachian Plateau | Great Lakes Plain/SW Tug Hill | Hudson Valley/

Catskills |

Northern Tier | Mohawk/Black River Valley | Grand Total |

| Hectares | 432,825 | 930,181 | 124,297 | 219,038 | 263,370 | 1,969,712 |

| % of Grand total | 0.22 | 0.47 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.13 | |

| Habitat in Hot Blocks (ha) | 130,808 | 401,055 | 52,756 | 81,059 | ||

| % Habitat in Hot Blocks | 0.30 | 0.43 | 0.24 | 0.31 | ||

| Habitat in Hot Block IBAs | 0.00 | 26,205.93 | 21,471 | 0.00 |

|

BCR 13 Forest |

Appalachian Plateau | Great Lakes Plain/SW Tug Hill | Hudson Valley/

Catskills |

Northern tier | Mohawk/Black River Valley | Grand Total |

| Hectares | 441,925 | 616,030 | 587,250 | 466,476 | 372,342 | 2,484,023 |

| % of Grand total | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.15 | |

| Habitat in Hot Blocks (ha) | 174,382 | 261,654 | 430,057 | 159,330 | 152,126 | |

| % Habitat in Hot Blocks | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.73 | 0.34 | 0.43 | |

| Habitat in Hot Block IBAs | 2,733 | 0 | 12,614 | 23,390 | 0 |

| BCR 14 Forest | Adiron-dacks | Great Lakes Plain | Hudson Valley | Lake Champlain | Mohawk/Black River Valley | St. Law-rence | Tug Hill | Grand Total |

| Hectares | 2,146,546 | 7,791 | 119,807 | 38,428 | 22,194 | 2 | 243,381 | 2,578,150 |

| % of Grand total | 0.83 | < 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.09 | |

| Habitat in Hot Blocks (ha) | 878,269 | 243,381 | ||||||

| % Habitat in Hot Blocks | 0.41 | 100.00 | ||||||

| Habitat in Hot Block IBAs | 123,965 | 3,000 |

| BCR 30 Forest | Lower Hudson | Coastal Lowlands | Grand Total |

| Total hectares | 67,733 | 93,022 | 160,755 |

| % of Grand total | 0.42 | 0.58 | |

| Habitat in Hot Blocks (ha) | 30,998 | 17,334 | |

| % Habitat in Hot Blocks | 0.46 | 0.19 | |

| Habitat in Hot Block IBAs | 1,505 | 12,030 |

| BCR 30 Shrub | Lower Hudson | Coastal Lowlands | Grand Total |

| Total hectares | 2,416 | 105,851 | 108,268 |

| % of Grand total | 0.02 | 0.98 | |

| Habitat in Hot Blocks (ha) | 61,453 | ||

| % Habitat in Hot Blocks | 0.58 | ||

| Habitat in Hot Block IBAs | 38,367 |

Appendix D. Complementarity Assessment

Percentages are the percent of a species’ predicted breeding distribution within

all potential IBA sites of the particular ecoregion.

| BCR 28 Shrub | Appalachian Plateau | |

| American Woodcock | limited habitat 697 ha (9%) | |

| Whip-poor-will* | limited habitat 113 ha (1%) | |

| BCR 28 Grass | Appalachian Plateau | |

| all species | ||

| BCR 28 Forest | Lower Hudson | |

| Black-throated Blue Warbler | not predicted in Lower Hudson | |

| Hudson Valley | ||

| Black-throated Blue Warbler | not predicted in Hudson Valley | |

| Hooded Warbler | not predicted in Hudson Valley | |

| Worm-eating Warbler* | not predicted in Hudson Valley | |

| Catskills | ||

| Hooded Warbler | not predicted in Catskills | |

| LA Waterthrush | limited habitat 6,000 ha (5%), only predicted w/in 100 m of hydrologic features | |

| Cerulean Warbler* | not predicted in Catskills | |

| Worm-eating Warbler* | not predicted in Catskills | |

| Appalachian Plateau | ||

| all species | ||

| BCR13 Shrub | Appalachian Plateau | |

| Common Snipe* | limited habitat 37 ha (0.3%) | |

| American Woodcock | limited habitat 100 ha (0.8%) | |

| Willow Flycatcher | limited habitat 430 ha (3.7%) | |

| Great Lakes Plain | ||

| Common Snipe* | limited habitat 124 ha (2%) | |

| American Woodcock | limited habitat 237 ha (4%) | |

| Northern Tier | ||

| Blue-winged Warbler | not predicted in St. Lawrence ecoregion | |

| American Woodcock | limited habitat 200 ha (0.4%) | |

| Willow Flycatcher | limited habitat 471 ha (1%) | |

| BCR13 Grass | Great Lakes Plain | |

| Common Snipe* | 168 ha (1.5%) | |

| Appalachian Plateau | ||

| Common Snipe* | no predicted habitat | |

| Upland Sandpiper* | limited habitat 213 ha (7%) | |

| Henslow’s Sparrow* | limited habitat 213 ha (7%) | |

| Northern Tier | ||

| all species |

| BCR13 Forest | Appalachian Plateau | |

| Common Snipe* | 80 ha (0.3%) | |

| Great Lakes Plain | ||

| all species | ||

| Hudson Valley | ||

| Cerulean Warbler* | not in Ashokan/Catskills or Moreau potential IBA sites | |

| Common Snipe* | limited habitat 187 ha (0.4%) | |

| Northern Tier | ||

| Baltimore Oriole | not predicted in Adirondacks, sufficient coverage in St. Lawrence and Lake Champlain | |

| BCR14 Forest | ||

| Adirondacks | ||

| Ruffed Grouse | limited habitat 498 ha (0.2%) | |

| American Woodcock | limited habitat 2568 ha (1%) | |

| Tug Hill | ||

| Bicknell’s Thrush* | no predicted habitat | |

| Blackpoll Warbler* | no predicted habitat | |

| Ruffed Grouse | limited habitat 617 ha (3%) | |

| American Woodcock | limited habitat 642 ha (3%) | |

| BCR30 Forest | Coastal Lowlands | |

| all required species | ||

| no bonus species | not predicted on Long Island | |

| Lower Hudson | ||

| all species | ||

| BCR30 Shrub | ||

| Coastal Lowlands | ||

| Brown Thrasher | not predicted in pitch pine habitat, but sufficiently covered in Long Island Pine Barrens IBA | |

| American Woodcock | limited habitat 1,000 ha (3%),sufficient coverage in other Long Island IBAs |

* denotes bonus species (see text).

Application in Geospatial Technologies Certificate

Posted on May 4, 2012 Leave a Comment

Completed Certification as a User/Analyst, see course list here.

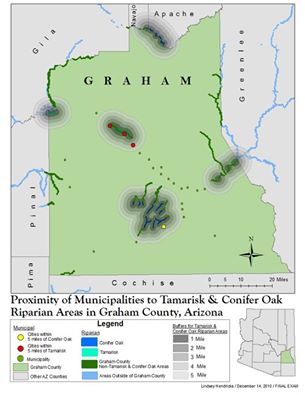

At Mesa Community College (MCC) from 2010 to 2012, I worked towards a certificate in Geospatial Technologies, under the guidance of program director Karen Blevins. The decision to enroll was based on a recommendation from the Audubon Arizona’s Director of Conservation, Tice Supplee, who was just beginning a project with Karen. Volunteering on a bird survey one day, Tice and I began a conversation on the topic and determine the opportunity was a perfect fit for me with my graphic design skills. It was then I realized that not only would I gain a new set of skills, building on my love of maps, the internship would provide real-world conservation experience with Audubon Arizona to analyze their Important Bird Areas (IBAs). This was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity that I could not pass up!

Through MCC’s 2-year Geospatial Technological certification program, I was able to establish a firm foundation of fundamental GIS skills such as database management, visual basics, SQL, python coding, spatial statistics, and remote sensing. Determined to understand all aspects of this technology, I worked very hard throughout the program to form a solid baseline for visualizing spatial patterns and grasping these geographical concepts. Alongside the certification, I was eager to participate in Karen and Tice’s lab immersing myself in real world conservation GIS throughout the 4 semesters. The involvement increased my confidence with the technology as I applied my newly gained skillset; building geodatabases, editing boundary shape files, and adding layers for spatial analysis (bird distributions, vegetation, ownership, topography, roads and rivers). Collectively the lab group completed over 50 Important Bird Areas and gained attention from the college with an article to highlight the experience.[1] The mentorship of both Karen and Tice has been priceless asset through my educational journey and leading me on a career path in GIS.

For my certification capstone, I worked on a regression analysis model for bird species of greatest concern for the state of Arizona based off a study in New York. Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI) highlighted Audubon New York’s study in an ArcNews article in 2004, “Audubon Uses GIS to Identify Important Bird Areas in New York State”.[2] With collaboration of Audubon New York’s IBA coordinator, Jillian Liner, and Tice Supplee, and invaluable advisement from Karen Blevins, I recreated a similar model for Arizona to determine location allocation of the state’s IBAs based various mathematical concepts and indices using bird conservation regions guidelines associated with vegetative land cover data and bird distribution data from Arizona Game and Fish Department.

In 2012, I took this model to McDowell Sonoran Field Institute[3] (MSFI) and analyzed the species of greatest concern for all vertebrate species (bird, mammal, reptile and amphibian) using data collected from the Arizona Game and Fish Department for the 30,000-acre preserve. This information helped guide the MSFI baseline data investigations for Flora and Fauna in Scottsdale’s McDowell Sonoran Preserve[4] that launched in 2012. It was rewarding when Melanie Tluczek, MSFI’s manager, handed me the published copy in 2015 mentioning that my maps helped guide the starting locations for fauna investigations, I was thrilled.

[1] https://www.mesacc.edu/news/press-release/important-bird-area-project-provides-learning-opportunity-mcc-students

[2] http://www.esri.com/news/arcnews/summer04articles/audubon-uses.html

[3] http://www.mcdowellsonoran.org/content/pages/fieldInstitute#sthash.4gn2f88C.EsyukZPq.dpbs

[4] https://s3.amazonaws.com/McDowellSonoranConservancyImages/fc947b63-7572-40fe-9f19-29339d412cea8207388897619413411.pdf

First semester Final Map

Christmas Bird Count

Posted on December 28, 2010 Leave a Comment

Since 2010, I’ve participated in in 3 Christmas Bird Counts for the Gila River area with The National Audubon Society’s state office, Audubon Arizona. The Christmas Bird counts is the nation’s longest-running citizen science bird project fuels Audubon science throughout the year.

The morning’s start around 4:30am traveling with my well informed birder to play calls listening for screech owls just before the sun breaks on the horizon. Some may imagine the screech owl mimics a high pitched sound, but the call sounds more like a bouncing ball. These mornings are a bit cold, even for the desert with average lows fall below 10 degrees Farenheit.

Some of my favorite moments are at the end of the day, when the birds begin to roost as the sun calls it a day. The circling pattern is hypnotizing, and provides a breath taking view as the sun paints the sky with varying shades of pinks, oranges and reds. It’s a memory that will stay with me forever.

http://www.azfo.org/CBC/PhxAreaCBCdescriptions.html

Gila River Christmas Bird Count. The Gila River circle is centered three miles east of Powers Butte and about the same distance south of Palo Verde. The count encompasses unincorporated Arlington and Palo Verde as well as part of the Town of Buckeye. This western Maricopa County count dates from 1981.

The Gila River winds through the middle of the count circle and provides excellent birding habitat. The Hassayampa River empties into the Gila upstream from Powers Butte. An added feature is the presence of the Robbins Butte Wildlife Area. Elevations range from approximately 700-1900 feet. This count typically records about 140 species.

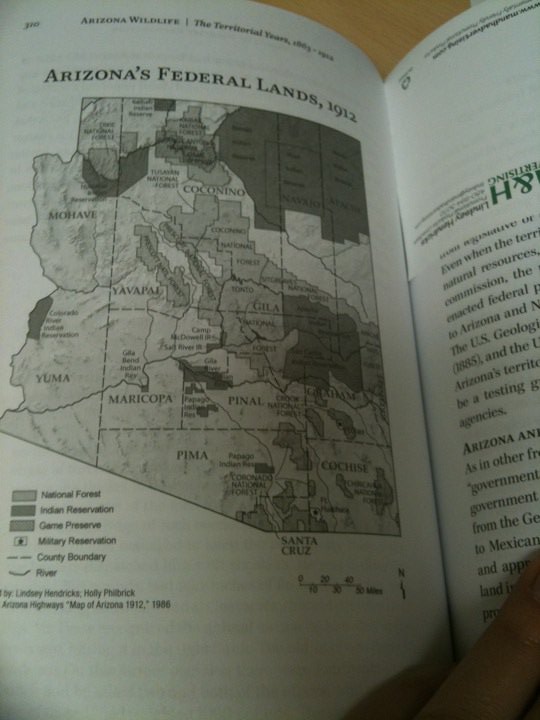

Arizona Wildlife

Posted on October 17, 2010 Leave a Comment

During my undergraduate degree, I decided to take a cartography class and during this cartography class it just so happened that one of my Conservation Biology professors, Dave Brown, needed some maps made for his next book published with Arizona Game & Fish.

I jumped at the chance to use this publication as my final project. This opportunity came about in 2003, the book, Arizona Wildlife was finally published in 2010. So grateful to be apart of his legacy of books for history of wildlife in Arizona from this naturalist hero.

Dave Brown taught my favorite class in my undergrad, Wildlife Techniques, half of a decade later he was name Educator of the Year. Currently, he’s on the advisory board for the McDowell Sonoran Conservancy so I’m lucky to still be in contact with him today and will be working on some dynamic maps for him in his current research.

http://www.gf.state.az.us/i_e/pubs/wildlifeHistory.shtml

Do you ever wonder what hunting and fishing were like in Arizona Territory? Did our pioneering forefathers find wildlife more plentiful then? Arizona Wildlife: The Territorial Years, 1863–1912 shows readers what it was like when most meals were obtained out-of-doors, and there were no paved roads, no large reservoirs and few restaurants. You may be surprised to learn that some wildlife species were always scarce and that others, now common, were non-existent then. Which ones were which? The answers make interesting reading.